WHY PAINTING NOW? – curated by Antonia Lotz

Why Paint

David Batchelor Andy Hope 1930

Andy Hope 1930

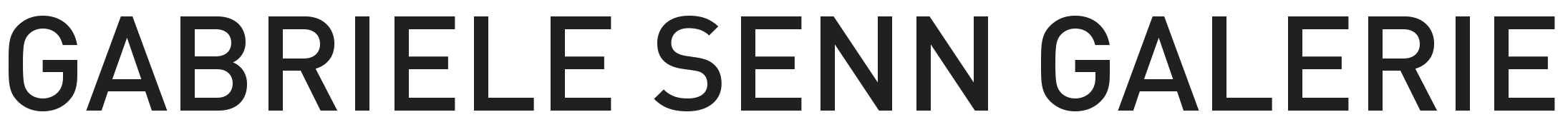

Time Machine (1), 2011

Lack, Öl auf Canvasboard

80 x 60 cm

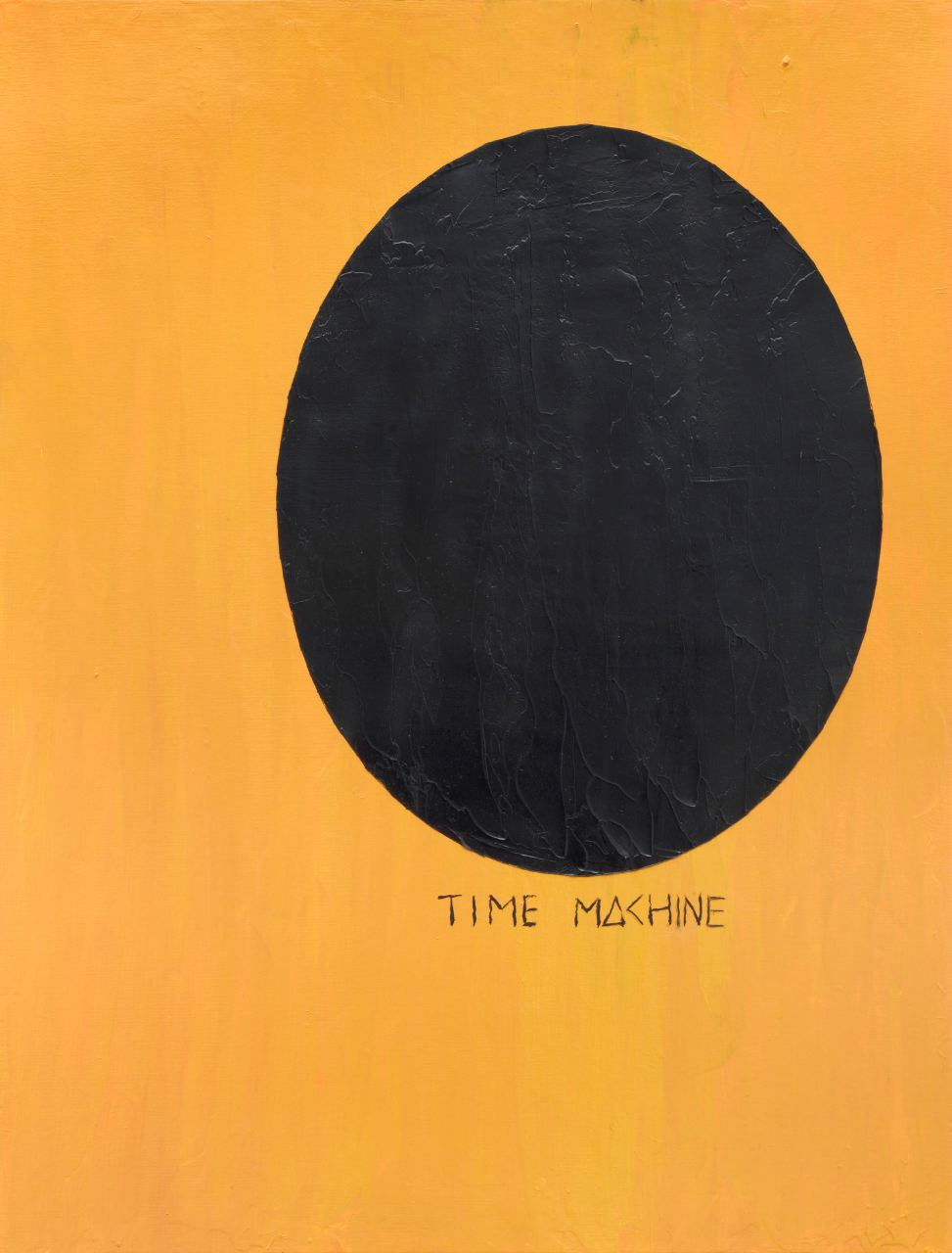

Andy Hope 1930

Time Machine (3), 2011

Lack, Öl auf Canvasboard

80 x 60 cm

Why paint colors?

Why paint walls?

Why paint and form?

Why paint houses?

Why paint flowers?

Why paint canvases?

Why paint sculpture?

Why paint ovals, Malevich? Why paint and sculpt? Why paint Sundays?

Why paint grey, white, or black? Why paint and think?

Why paint paper?

Why paint suffering?

Why paint sober?

Why paint concrete? Why paint and speak? Why paint dates?

Why paint transparently? Why paint stripes?

Why paint red?

Why paint bodies?

Why paint abstractly? Why paint painters?

Why paint yellow?

Why paint and sing?

Why paint beauty?

Why paint portraits?

Why paint blue?

Why paint monotone? Why paint cruelty?

Why paint numbers? Why paint mama?

Why paint boring?

Why paint wet?

Why paint squares? Why paint flatly?

David Batchelor

31 (black) 17.06.11, 2011

glänzender und matter Lack auf Dibond

76 x 61 cm

zweiteilig

David Batchelor

8 (yellow) 28.03.11, 2011

glänzender und matter Lack auf Dibond

79,3 x 60,7 cm

„Die Malerei, die Materialität der Farben, die visuelle Qualität der Farbe, sie liegen tief in unserem Organismus. Ihr Aufflammen kann mächtig und fordernd sein. Mein Nervensystem ist von ihnen geprägt. Mein Gehirn brennt von ihren Farben.“ (K. Malewitsch, 1915)

Kasimir Malewitschs Schwarzes Quadrat (1915) auf weißem Grund ist die Nullform, der Nullpunkt und zugleich Startpunkt des Suprematismus: Mit diesem Werk hat sich der Künstler von aller Gegenständlichkeit befreit um eine neue, „gegenstandslose Welt“ zu schaffen. Das Schwarze Quadrat bildet zusammen mit dem Schwarzen Kreis und dem Schwarzen Kreuz die Grundlage für das künstlerische System des Suprematismus. Kreis und Kreuz entstehen aus dem Quadrat, einmal durch dessen Drehung und einmal durch dessen Teilung. Der weiße Grund der Bilder symbolisiert die Unendlichkeit des Raums, in dem alle geometrischen Flächen schweben. Der Traum von der Loslösung der Erdanziehungskraft und der Bewohnung des Kosmos sind Teil der suprematistischen Utopie, die Malewitsch um 1920 zusammen mit der Gruppe Unowis (Bestätiger der Neuen Kunst) mit Entwürfen für alle Bereiche des Lebens und Wohnens umzusetzen begann. Im Jahr 1928 knüpft Malewitsch an seine Anfänge in der Kunst an und kehrt zur figurativen Malerei zurück. Seine späten Bilder zeigen Menschen wie Bauern und Sportler oder auch Häuser in angedeuteten Landschaften. Die suprematistische Farbenlehre und Systematik der Teilung einer Form in viele weitere sind maßgebend für den Aufbau und die Farbgebung der Figuren – ihre Gesichter sind auf verschieden farbige ovale Flächen reduziert.

Das Werk von David Batchelor (*1955 in Dundee, lebt in London) umfasst Fotografie, Malerei, Arbeiten auf Papier und dreidimensionale Strukturen. Die Auseinandersetzung mit Farbe, Urbanität, Abstraktion und der Tradition des Monochroms ist in fast allen seinen Arbeiten präsent. Die ihrer Entstehung nach durchnummerierten und mit Datum betitelten Blobs bestehen aus auf Dibondplatten gegossener Lackfarbe, ihre rechteckigen Sockel aus dünn aufgetragener mattschwarzer Farbe. In diesen Ovalen fallen Gegenpole von Antiform und Geometrie, von Präzision und Prozess sowie Skulptur und Malerei zusammen in der Beschäftigung mit der Materialität sowie Mannigfaltigkeit von Farbe. Zu Batchelors Ausstellungen der letzten Jahre gehören Flatlands, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh (2013/14); Magic Hour, Gemeentmuseum, Den Haag (2012); Chromophilia: 1995–2010, Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro (2010); Backlights, Galeria Leme, São Paulo (2008); Color Chart, Museum of Modern Art, New York/Tate Liverpool (2008/09) und Unplugged, Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh (2007). Chromophobia, Batchelors Buch über die Angst vor Farbe erschien 2000 bei Reaktion Books, London, wo auch sein neues Buch The Luminous and the Grey 2014 erscheinen wird.

Die Gemälde, Skulpturen, Collagen und Zeichnungen von Andy Hope 1930 (*1963 in München, lebt in Berlin) nehmen auf verschiedene konkrete kunsthistorische wie populärkulturelle Quellen Bezug. Zwei bedeutende, mit dem Jahr 1930 verknüpfte Referenzsysteme für Andy Hope sind: Der Aufstieg des Comics als Massenmedium und das Ende der Projekte des Suprematismus und des russischen Konstruktivismus, dessen Wiederbelebung und Reformulierung der Künstler im Sinne einer „Sub- History“ (Hope) betreibt. Die vier Time Machine Bilder, die aus schwarzer Ölfarbe gespachtelte Ovale auf orange bemalten vorgefertigten Leinwänden zeigen, gehören zu der Serie der Medleys: Werke, in denen Hope seit ein paar Jahren Motive und Kompositionen seiner früheren Arbeiten wiederholt und neu durcheinandermischt. Die ursprüngliche Version von Time Machine, ein schwarzes Oval auf weißem Grund zeigt Malewitschs Schwarzes Quadrat, das sich durch die Gravitation der Zeitreise des Künstlers verzogen hat. Zu Hopes Ausstellungen der letzten Jahre gehören: Fruits de la Passion, Centre Pompidou, Paris (2012/13); Andy Hope 1930 When Dinosaurs Become Modernists, Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh (2012); Medley Tour by Andy Hope 1930, kestnergesellschaft, Hannover (2012); Detour – Landscape in Progress II, CAC Contemporary Art Club, Wien (2011) und Andy Hope 1930, Sammlung Goetz, München (2010).

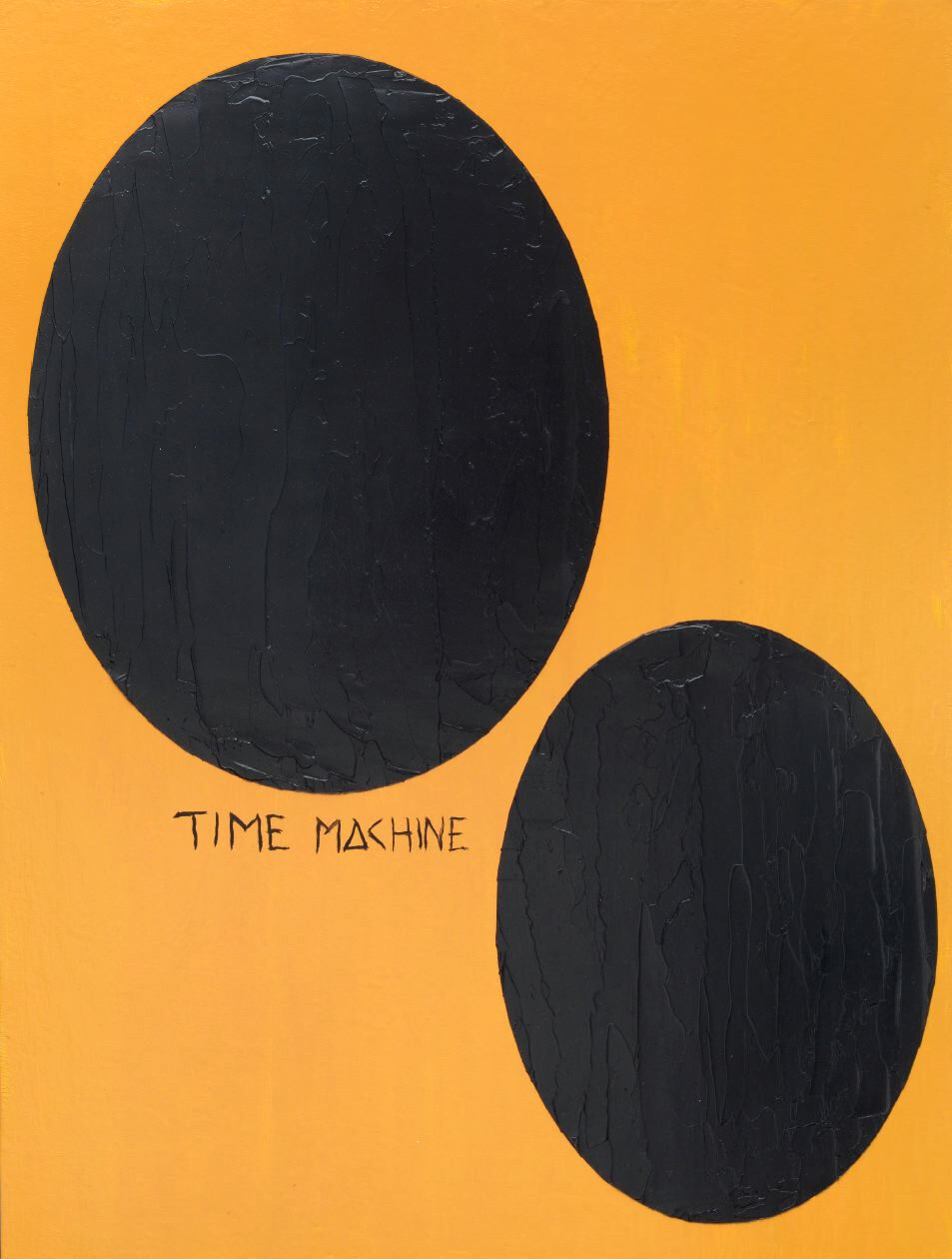

Andy Hope 1930

Survivors, 2009

Marker auf Papier

24,2 x 16,5 cm

Andy Hope 1930

Ernter des Morgens, 2009

Marker auf Papier

24,2 x 16,5 cm

“Painting, the materiality of colours, the visual quality of colours, they lie deep within our organism. In case they are lightened up, they might be powerful and demanding. My nervous system is shaped by them. My brain is enflamed by their colours.” (K. Malevich, 1915)

Kasimir Malevich’s Black Square on a White Ground (1915) is the form of origin, point zero and, also, the starting point of Suprematism. It is with this piece that the artist liberated himself from all concreteness in order to create a new shapeless world. Black Square, together with Black Circle and Black Cross, forms the basis for the artistic system that is Suprematism. Circle and cross derive from the square, once by setting it into motion, once by dividing it. The white background of the paintings symbolizes the infinity of space in which all geometric forms float. Part of this suprematist utopia, which Malevich started to implement with his followers, the group UNOWIS (meaning “Champions of the New Art”), for all areas of life and living from 1920 onwards, is the dream of detaching oneself from gravity, of inhabiting the cosmos.

In 1928, Malevich recalls his beginnings in art and returns to figurative painting. In his later works, he shows people such as peasants and sportsmen but also houses in landscapes that are merely hinted at. The suprematist colour doctrine and system of dividing one form into many more are crucial for the composition and the choice of colour of the figures – their faces are reduced to various coloured oval surfaces.

The oeuvre of David Batchelor (born in Dundee, 1955; resident in London) covers photography, paintings, works on paper and three-dimensional structures. His way of dealing with colour, urbanity, abstraction and the tradition of monochromes can be seen in nearly all his works. His Blobs which he has chronologically numerated, their titles being their dates, only consist of varnish that he has poured onto dibond plates and their rectangular pedestals made from thinly applied matte black colour. The antipole of antiform and geometry, of precision and process as well as of sculpture and painting all boil down to working with the materiality and the multiplicity of colour. Batchelor’s latest exhibitions include Flatlands, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh (2013/14); Magic Hour, Gemeentmuseum, Den Haag (2012); Chromophilia: 1995–2010, Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro (2010); Backlights, Galeria Leme, São Paulo (2008); Color Chart, Museum of Modern Art, New York/Tate Liverpool (2008/09) and Unplugged, Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh (2007). In 2000, Batchelor published his book Chromophobia, which deals with the fear of colours, with Reaktion Books, London where he will also publish his new work The Luminous and the Grey in 2014.

The paintings, sculptures, collages and drawings of Andy Hope 1930 (born in Munich, 1963; resident in Berlin) make reference to various concrete sources from the field of art history or popular culture. Two of his essential systems of reference, both of which share the year 1930, are the following: The rise of comics as a mass medium and the end of the projects of Suprematism as well as of Russian Constructivism, which the artist tries to revive and reformulate in terms of a “sub-history” (Hope). His four Time Machine paintings, which show ovals primed from black oil paint on orange-coloured canvas, are part of his series Medleys: These are paintings in which Hope has reverted to some motifs and compositions from earlier works, which he now combines in a new way. His original version of the Time Machine paintings, a black oval on white ground, shows Malevich’s Black Square, distorted by gravity as a consequence of the artist’s time travels. Hope’s latest exhibitions include Fruits de la Passion, Centre Pompidou, Paris (2012/13); Andy Hope 1930 When Dinosaurs Become Modernists, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (2012); Medley Tour by Andy Hope 1930, Kestner Society, Hannover (2012); Detour – Landscape in Progress II, CAC Contemporary Art Club, Vienna 2011) and Andy Hope 1930, Goetz Collection, Munich (2010).